Feature Story Focus on the cargo and sustainability: Trends in the heavy-lift segmen…

페이지 정보

작성자 최고관리자 댓글 0건 조회 974회 작성일 24-06-14 15:54본문

Good news for the multipurpose cargo carrier segment: Following a brief uptick in 2021–22 triggered by “container euphoria”, and a marked drop in freight and charter rates last year, there are now indications that the MPV market may be stabilizing at a viable level. Industries like renewables, but also conventional energies including oil, natural gas, general mining, nuclear power as well as the heavy industry, are all experiencing an increase in demand. Newbuild orders are slightly on the rise.

Rising demand of heavy cargo transport – rising newbuild costs

This also applies to the small, yet important heavy-lift segment, which comprises highly specialized and individually designed ships with deadweights between 5,000 and just under 40,000 dwt, and crane capacities ranging from 100 to 1,500 tons. Around the world, about 480 vessels of this type are currently in service, with an average age of roughly 15 years. Shipyard orderbooks are listing some 50 newbuild projects, meaning a potential for more orders is seen, thus coping with the new requirements from the cargo side, as well as the expected phase-out of elderly ships.

However, rising demand for newbuilds of other ship types has prompted yards to raise their prices substantially. China has been able to grow its footprint as the leading shipbuilding nation in general, including in the MPV segment. It is my assessment that European yards would be unable to compensate for any capacity shortfalls, having lost their ability to compete with China in this specialized segment, whilst new players, like Indian shipyards, could enter the market soon.

Balancing capacity and sustainability in heavy-lifter design

Heavy lifters are designed specifically for carrying project cargo. As cargo units are becoming larger, heavier and more complex, newbuilds must meet ever greater challenges in terms of cargo hold length limited by structural integrity and damage stability. At the same time, the vessel design must ensure the utmost cargo and loading flexibility as well as loading and unloading efficiency to maximize profitability and sustainability – all this with the industry heading towards decarbonization. As a consequence, design complexity increases significantly. It goes without saying that there are natural limitations to further growth of cargo holds; not everything that modern engineering can accomplish is commercially feasible.

Optimizing newbuild designs: DNV’s approach to efficiency and flexibility

DNV recommends optimizing newbuild designs based on the operating and cargo profile while ensuring that the time in port can be minimized. One long cargo hold instead of two shorter ones makes sense; the hatch covers should be optimized for project cargo based on the accelerations specified by DNV’s widely recognized DNV-ST-N001 standard. A multiple load line approach increases flexibility further. Some designs try to combine the benefits of deck carriers with heavy-lifter concepts through maximizing the free deck area by arranging the deckhouse forward, extending the cargo deck beyond the vessel’s beam or removing “obstacles” like the funnel.

Deck carriers: A cost-effective and versatile addition to heavy-lifter fleets

When project cargo is too large and heavy for heavy-lift vessels, open-deck carriers show their muscle. Because of their simple design they can be built at a relatively low cost. Operators therefore like to use deck carriers as an add-on to their heavy-lifter fleet. In the project cargo business, keeping one’s fleet versatile is generally advisable because many projects involve a combination of bigger and smaller cargo items, some of which do not require an expensive specialized vessel. A varied fleet allows the operator to ensure optimal utilization when selecting vessels for a given project.

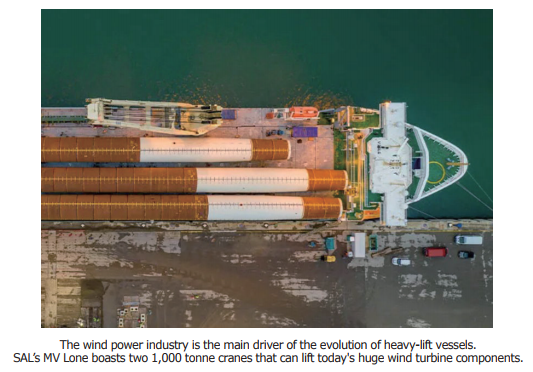

Wind energy drives the segment

In recent years there has been a trend to equip heavy-lift vessels with bigger, stronger cranes, especially in response to the growing requirements of a burgeoning wind industry. As wind turbines get bigger and more powerful, their foundations, towers, nacelles and rotor blades are also taking on more gigantic dimensions. A large nacelle may weigh more than 700 tons today; forecasts see them at 1,400 tons or more by 2030. There are not many vessels that can carry such cargo. But since the medium-term demand is difficult to foresee, owners are hesitant to order ever larger ships with even greater capacities without long-term commitment from cargo owners.

More efficient on-board cranes reduce energy consumption

Current newbuild investments focus on ships with taller cranes with capacities ranging between 500 and 800 tons. Very large cranes are expensive and associated with major challenges in terms of design and operation. This is a point where the expertise and advice of a classification society such as DNV is indispensable. It may be necessary for ships to carry pontoon systems along to ensure stability when loading and unloading.

More often, modern, smart on-board cranes are fully electrically operated, which means they only consume energy when moving. This makes them considerably more efficient than electro-hydraulic cranes. Furthermore, if equipped with regenerative drives they can produce energy when lowering loads, similar to regenerative brakes in hybrid cars.

Propulsion and power plant options to reduce fuel consumption

Many heavy lifters cruise at “eco speed” in the range of 11–13 knots and have a variable draught of six to eight metres. Diesel-mechanical propulsion using efficient two-stroke engines, frequently combined with a shaft generator or power-take-off(PTO), are common. Concepts including power-take-in(PTI) are an option; combined with a battery pack, this approach would enable both main engine peak shaving and brief emission-free operation in sensitive areas. Hybrid systems including batteries, fuel cells or gensets operating on carbon-neutral fuels are further options to implement a decarbonization strategy.

Decarbonization options for heavy lifters

The IMO decarbonization regulations(in particular, the EEXI and CII indices) currently grant a special exempt status to certain specialized vessels such as heavy lifters. Nevertheless, the EU emission-trading scheme(ETS) applies fully in European waters, and future regulations such as FuelEU Maritime will also be relevant for the heavy-lift segment.

It is assumed that many remote destinations of project cargo are unlikely to provide infrastructure for bunkering LNG, ammonia or other alternative fuels within the next decade. Yet, we can see a trend towards designing newbuilds ready for future retrofitting of a methanol fuel system.

After all, efficiency, sustainability and economic viability are core concerns for this as for all other ship types, and many of the common optimization measures apply here as well.

Expert advice is crucial for increasingly complex ship designs

The fleet development mentioned at the beginning indicates that the fleet for extremely large and heavy cargo is in need of additions. As for the design of the next generation of ships, the demand from the cargo side will decide where the development will go. With the lion’s share of all heavy-lift vessels in its class, DNV has the in-depth knowledge and experience to help owners make well-informed choices to ensure their newbuilds will be well-prepared to compete successfully.

A number of DNV class notations are available to extend the capabilities and reach of heavy-lift ships. Examples include the DNV ship type notation “Multipurpose Dry Cargo Ship”, which includes specific design requirements for heavy lifters, as well as class notations such as “Hatchcoverless” and “Stability Pontoon”.

■ Source: DNV www.dnv.com